My first year as a law professor was in 2005. A lot has since changed in sports law.

Back then, sports law was a niche topic. Many law schools didn’t offer the course. It was neither a heavy hitting topic like constitutional law or evidence, nor one that might lead to a job, like tax or immigration law. Sports law was the rare “fun” course in curriculums that, for understandable reasons, focused mainly on bar exam readiness.

I also didn’t expect to become a “sports law professor.” Although I had been an attorney on the legal team for Maurice Clarett in his lawsuit against the NFL and represented other clients in sports-related disputes, relatively few law schools employed full time sports law professors. They typically used adjuncts instead.

When I went on the tenure-track teaching market in 2004, I pitched myself mainly as a labor, employment, antitrust, and food and drug law candidate. I wanted a job, after all. Mississippi College School of Law hired me, and I was thrilled when Dean Jim Rosenblatt said I would teach sports law and encouraged me to embrace the topic.

And so I did.

I taught students how the NCAA was largely immune from antitrust litigation and that college athletes couldn’t sign endorsement deals since they were amateur “student-athletes.” College athletes gaining a cut of revenue, becoming recognized as employees and forming unions weren’t on the radar screen. In fact, mentioning those ideas on exams would have been marked in red as “wrong.”

I also taught how sports betting was generally illegal and that players testing positive for marijuana was like testing positive for cocaine, heroin and other drugs of abuse. Back then players’ unions would go on strike, too, I explained.

There were a lot of sports law topics I didn’t teach. While we talked about athlete injuries, including when football players “got their bell rung,” concussion and painkiller litigation were years away. There were privacy issues to examine but not connected to something we’d later call “social media” or to future devices like iPhones and Fitbit wearables.

Beyond individual player-rights issues, the legal mechanics of franchise sales and relocations came up, but private equity buyers and sovereign wealth funds were yet to be dreamt of. Likewise, the Sports Broadcasting Act of 1961 and legal issues in cable and satellite broadcasts were topical, but disputes over streaming live sports were for another day.

And, no, I didn’t teach them about the law and science of slightly underinflated footballs. If only I had the foresight!

I also became sensitive to the depiction of sports law as not being a real thing.

Some legal commentators viewed sports law as having no center. It concerned other areas of law occurring in the sports context, they said. For instance, Curt Flood’s historic case against Major League Baseball wasn’t sports law, but instead an antitrust case involving a baseball player. The NBA’s case against Motorola was a copyright infringement case related to basketball games.

I remember meeting Justice Antonin Scalia at a reception in Jackson, Miss., in 2006. He asked me which courses I taught, and I said sports law. Scalia replied, “Sports law, what’s that?”

Fast forward to 2025. Sports law is undoubtedly a real topic. The course is regularly offered by law schools, and the number of sports law professors expands every year. Whereas 20 years ago there were only a handful of law firms with robust sports law practice groups, now they’re common among large and medium-sized firms.

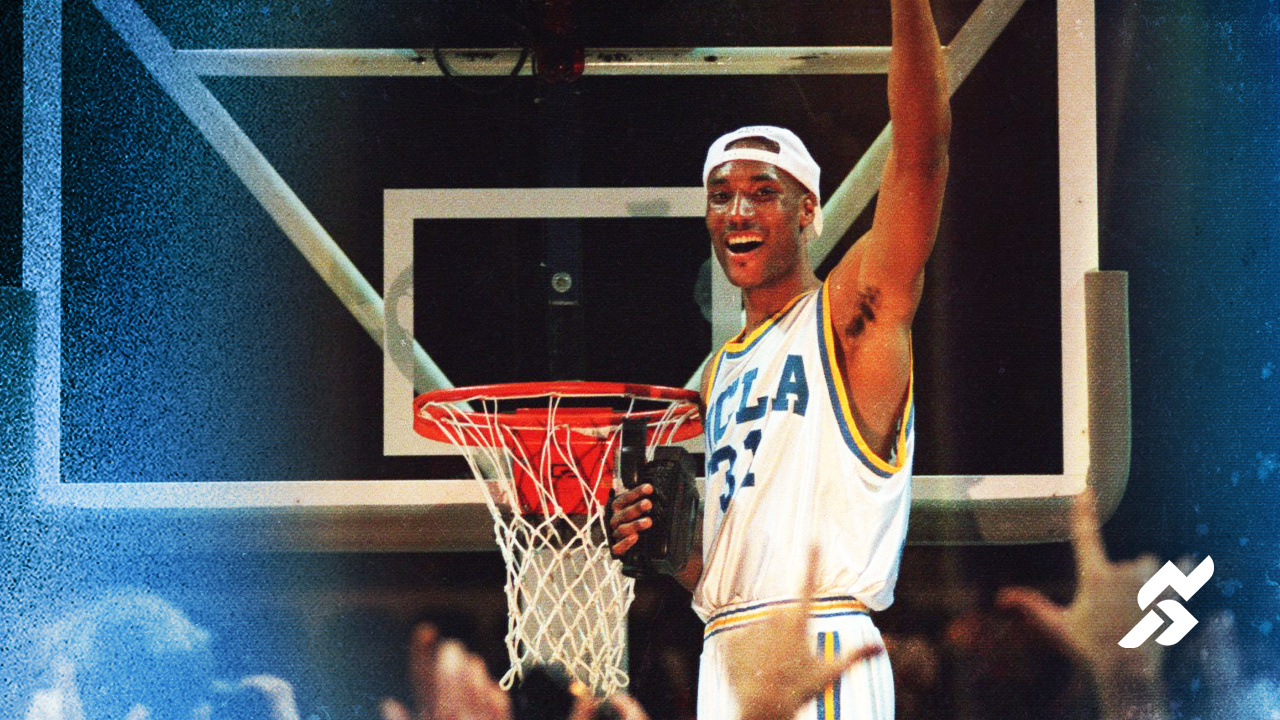

Part of the growth reflects the enormous amount of money invested in sports, which in turn sparks more client opportunities for attorneys and law firms. It also highlights how sports law has become its own unique field. Through a series of lawsuits that began with Ed O’Bannon’s historic case over the use of college athletes’ NIL in video games and that continues to this day with college athletes wanting to keep playing so they can earn NIL and revenue shares, college sports has morphed into a unique and still evolving creature for legal study.

It’s not just college sports that are experiencing tectonic change. Pro leagues, which have historically used arbitration to resolve disputes out-of-court, are now seeing major pushback through lawsuits brought by Brian Flores and Jon Gruden. They’re also handling legal battles over the streaming of games and the exclusivity of game broadcasts.

Much of the playbook for sports law has been overhauled over the last two decades. Don’t get too comfortable with the new schemes: Given the rapid pace of change in sports, expect many rewrites ahead.